Humayun’s Tomb: A Masterpiece of the Mughal Era

Since the beginning of the eleventh century, massive tombs have been a part of the Muslim architectural world. Red sandstone and white marble structures dating back to the fourteenth century can be found in various parts of India. The Timurid dynasty contributed to many radially symmetrical buildings—tombs and palaces—in many parts of Iran and Central Asia. However, before the construction of Emperor Humayun’s tomb, no structure incorporated all these elements in a single monument . Documented as the first ever tomb built for a Mughal emperor, this structure is considered to be an inspiration for the most well-known example of Mughal architecture, the Taj Mahal.

But the significance of Humayun’s tomb goes way beyond than just being a prototype for the Taj Mahal. This tomb was the first structure in which the slightly bulbous and double dome, a feature borrowed from Persia and Samarkand, was introduced in India. It is also the first example of a tomb set within a cross-axial garden in India. Its enormous scale and radially symmetrical plan makes the building stand out as one of the greatest examples of the Mughal royal mausoleum building style.

There has been a lot of debate about the identity of the builder of the tomb. Scholars have argued that it was Haji Begam, Humayun’s widow who had commissioned this mausoleum. However, according to Akbar Nama (2: 367), written by Emperor Akbar’s official biographer Abu’l Fazl, Haji Begam was on a pilgrimage to Mecca during much of the construction period of the tomb. This is confirmed by both Abu’l Fazl and Father Monserrate, a Jesuit priest who resided in Emperor Akbar’s court during the early-1580s. Although, there are various reports regarding the construction period of the tomb, the common belief is that construction began in 1565, nine years after Humayun’s death. The work was completed in 1572, at a cost of 1.5 million rupees at the time. Given the magnificence, the huge cost and innovation in planning of the mausoleum, it was evident there was a patron involved—this was none other than Humayun’s son and successor, Akbar.

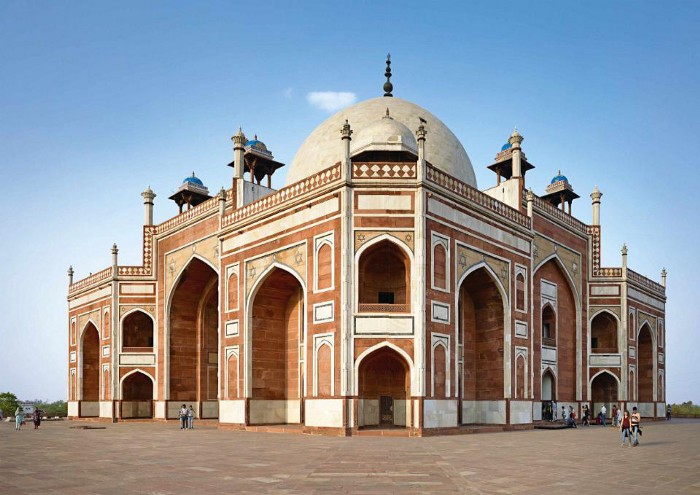

A combination of Persian architecture and indigenous building styles is perhaps another of the many striking features of this grand mausoleum. One contemporary historian, ‘Abd al-Qadir Badauni, mentioned that the structure was designed by Mirak Mirza Ghiyas, an architect of Iranian descent, who was brought from Herat in northwest Afghanistan.

The location of the tomb also happens to be on an incredibly significant archaeological setting; the shrine of the 14th century Sufi Saint, Hazrat Nizamuddin Auliya is located just outside the main complex of the tomb. The tomb itself sits on a flat plain of Delhi, near the banks of the Jamuna, surrounded by a series of Sultanate and Mughal monuments. Due to the widespread belief that it was auspicious to be buried near a saint, the location has turned out to be the densest ensemble of Islamic medieval buildings in India, thanks to all the tomb constructions, spanning seven decades.

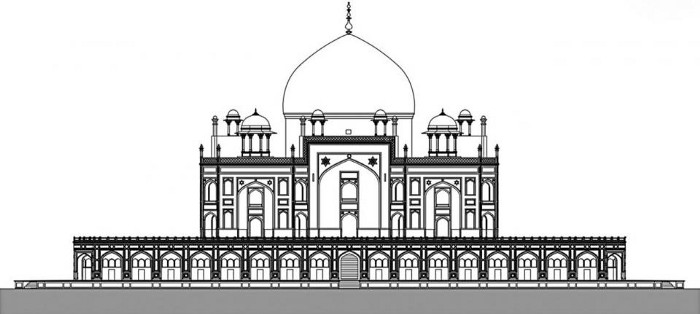

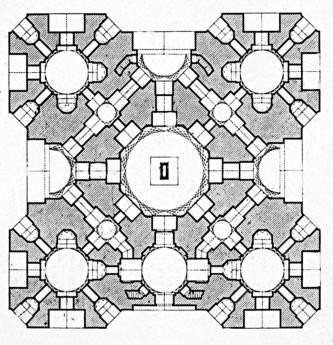

The tomb stands on a large plinth, which, at a height of 6.5 metre and width of 99 metre, is a terraced platform with two deep vaulted cells on all four sides. In spite of the fact that the tomb is basically a square structure, it appears to be octagonal in shape due the chamfered edges. Four distinct octagonal units separated by four recesses make up the mausoleum, with the entrance through the recess located in the centre of the southern facade.

Topping off the mausoleum is the 42.5 metre high Persian double dome, flanked by pillared kiosks, or chattris, which is a distinctly Indian architectural feature. This combination of Persian and Indian architectural styles work beautifully together, thus making Humayun’s Tomb a great example of a hybrid of styles of two separate cultures.

Contrast is one of the key elements the architect had in mind when designing the mausoleum. The exterior dome is made of purely white marble, while the rest of the building is of red sandstone, with white and black marble and yellow stone detailing. Additionally, the symmetrical and simple exterior design is distinctly the opposite of the complex interior floor plans. Two radially symmetrical floors make up the interior of the building. A central domed chamber with the emperor’s tomb in the middle and four corner rooms comprise the first floor. The second floor consists of a complex system of halls and passageways surrounding the tomb’s central chamber. The large corner rooms as well as the numerous cells at the plinth level are a clear indication that the structure was originally designed to accommodate several graves. As a result, Humayun’s tomb is also referred to as the “dormitory of Mughals”, since over 150 Mughal family members are buried there.

Persian style is once again evident in this complex in the Char-Bagh (Four Gardens), a quadrilateral garden layout inspired by the gardens of Paradise mentioned in The Holy Quran. Causeways divide the gardens into four sections, with shallow water channels connected to pools, located at the centre of each causeway. Each of the four sections in the 30 acre garden is further divided into smaller squares with pathways. With the synthesis of garden and mausoleum, Humayun’s tomb became one of the unique ensembles of Mughal garden-tombs. As a matter of fact, this style was so much favoured that it was repeated fifty years later at the tomb of Itimad al-Dawla (Agra, 1626-28) and the Taj Mahal (Agra, 1632-43).

For Humayun’s son and the patron of this tomb, Akbar, there were two purposes behind building this great structure: to commemorate his father’s legacy as well as to make a political statement. By building the tomb at such a large scale, Akbar wished to represent the range and scope of the empire, as well as establish his personal goals and alliances. Akbar’s dynastic origins are defined by the symmetrical plan and double dome, while the red sandstone and white marble represent his Indian origins.

By late 20th century, the magnificent tomb had fallen into a state of dilapidation. The masonry and stonework were broken and the gardens were run down. Additionally, vandalism and illegal encroachments were taking place, which posed a serious threat to the preservation of the mausoleum. In 1997, research for restoration work was taken up by the Aga Khan Trust for Culture (AKTC), in collaboration with the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI). Restoration began in 1999 and was completed in 2004, with the gardens fully restored as well.

Although Humayun’s Tomb stands as a precursor to the Taj Mahal, the most widely celebrated of Mughal architecture, for many historians, as well as myself, this building deserves to be known for what it is, rather than what it inspired. Perhaps art historian, Glenn Lowry has described it best in his dissertation titled The Tomb of Nasirud-Din Muhammad Humayun, “….its combination of boldness and refinement, energy and strength gives the building its power. That its parts vary in the degree of their success does not detract from the monument’s forcefulness or its attempt to create an entirely new approach to architecture in India.”