Women in Architecture —Where Do We Stand?

Gender disparity in the architecture profession has been an ongoing debate since a long time. In the year 1991, when the Pritzker Prize was awarded to Robert Venturi of Venturi, Scott Brown and Associates, the Pritzker committee chose to ignore the contribution of the other half of the firm’s namesake — his wife and partner, Denise Scott Brown.

In her essay titled ‘Room at the top?’ Denise Scott Brown shared her frustrations of being overlooked because of her gender, despite being as brilliant as her husband. Many architectural reviews often omitted her name from descriptions of projects where both she and her husband worked together diligently. When others told her to brush these things off, she asked if such little recognition would be enough for her male colleagues. “What would Peter Eisenman do if his latest article were attributed to his co-editor, Kenneth Frampton?” she challenged.

Statistics tell us the scenario is worse than we imagined. Only two female architects have won the Pritzker Prize, in its 34 years history. According to a 2012 survey by American Institute of Architects (AIA), only 16% of the licensed architects in the US are women, whereas 43% of architecture students are female. According to The Architect’ Journal’s annual Women in Architecture survey, in the UK, only 21% of the architects are women.

Work-life balance was identified as the main reason women are so underrepresented in this profession. Architecture education takes about five to seven years to reach completion. Another few years of work experience are needed before one can apply for the licensing exam. This is a time consuming process and it coincides with a woman’s childbearing years. Therefore many women have to make a choice between being a mother and being an architect. It is a tough decision to make and very few women can find the balance between work and family and are able to continue their profession. According to a diversity report published by AIA, published in January 2016, 70% of women partaking in the survey said they would leave the field if the long hours make it difficult to start a family.

One unique thing about working as an architect is that it is not a nine-to-five job. If it were, it would have been a lot easier for women to pack up work after five and go home to look after their family. Practicing architecture is a 24-hours-long process, a never ending cycle of brainstorming and coming up with new ideas. So it is hard to think about ergonomics and building materials when you have got a screaming toddler to take care of.

After going through the lengthy schooling and licensing process, many women face sexism and discrimination in the work place. In some cases, it starts even before a woman is hired for the job. As I peruse through advertisements for job vacancies for architects, I become disappointed because 7 out of 10 jobs ask for male applicants only. During one of my interviews at a firm, one of the preliminary questions I was asked was regarding my marital status. When I asked how that is relevant, the interviewer apologized and sheepishly replied that many female employees move abroad after getting married. So, training and hiring them is often, I quote, “a waste of time for the firm.”

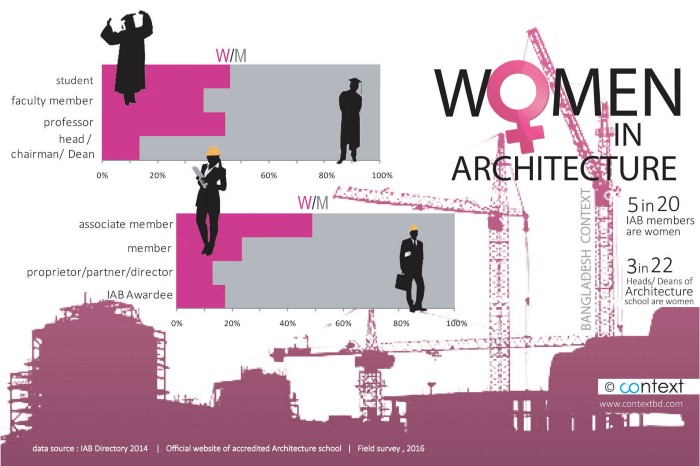

Architecture education in Bangladesh began in the year 1962, with the opening of the Department of Architecture of the Faculty of Architecture and Planning at Ahsanullah Engineering College, which is known as BUET, in present day. In the first ever batch, out of the 22 students, only 3 of them were women. In a way, architecture education paved the way for co-education in engineering schools of Bangladesh. Yet, today’s statistics paint a very disappointing picture. According to the directory of Institute of Architects Bangladesh (IAB), the percentage of female architects who are full licensed members is a meagre 23.5%, compared to the staggering 76.5% of full members who are male architects.

Marina Tabassum, renowned architect and founder of Marina Tabassum Architects (MTA), said at an interview given during the 2014 National Architecture Conference in Perth, that “…women are absolutely fantastic to have in the office. They are responsible and very systematic about everything, but they don’t come to practice permanently. Either they drop out or do a balancing act between supporting their family at the same time as doing a nine-to-five job.”

There are several things that can be done to rectify the situation. Women with families and children can be given flexible working hours. More widespread organizations can be opened up where female architects support each other and refer each other for projects, which will create a strong networking between them. We need to stop thinking of the architecture profession as an exclusive boys club. Brilliant architects like Denise Scott Brown must be given proper recognition because of the great designer they are, and not just as ‘the architect’s wife’. Women create a social impact in workplaces because of their compassion and their abilities to connect to people at all levels. Architects are creative individuals and truly unique professionals. We should not let something as inconsequential and trivial as the matter of gender hold us back. Once we let go of such narrow-mindedness, the profession will be home to more people with innovative and distinctive ideas.

Works Cited :

[1] Denise Scott Brown, Room at the top? Sexism and the Star System in Architecture, 1989.

[2] Diversity in the Profession of Architecture, Executive Summary, 2016, by the American Institute of Architects.

[3] The Architect’s Journal’s Women in Architecture annual survey, 2016

[4] Directory of Institute of Architects Bangladesh, (IAB), 2014

[5] Rafique Islam, The First Faculty of Architecture in Dhaka, 2010