Cities and their Imagibilities

Le Corbusier’s Towards a New Architecture, originally published in 1923, emerged around the same time as fascism and colonial regimes were developing in Europe as well as other parts of the world. A lot of the general dogma surrounding colonization was infiltrating the conversations about architecture during that period. As a result of which, Corbusier mentions terminologies in his book that were a result of the socio-political environments of his time. This is also perhaps why in his book, he distinguishes that ornamentation on walls is for “peasants and savages,” while things like a well-tailored suit or books is for “the civilized man.”[1]

Corbusier also reminds the architect of three principles for modern architecture: simple masses that can be seen in light, geometric surfaces enveloping those masses, and a plan which brings order for the whole design. Adhering to these principles is necessary because according to him, “Modern life demands a new form of plan, both for the house and the city.”[2]

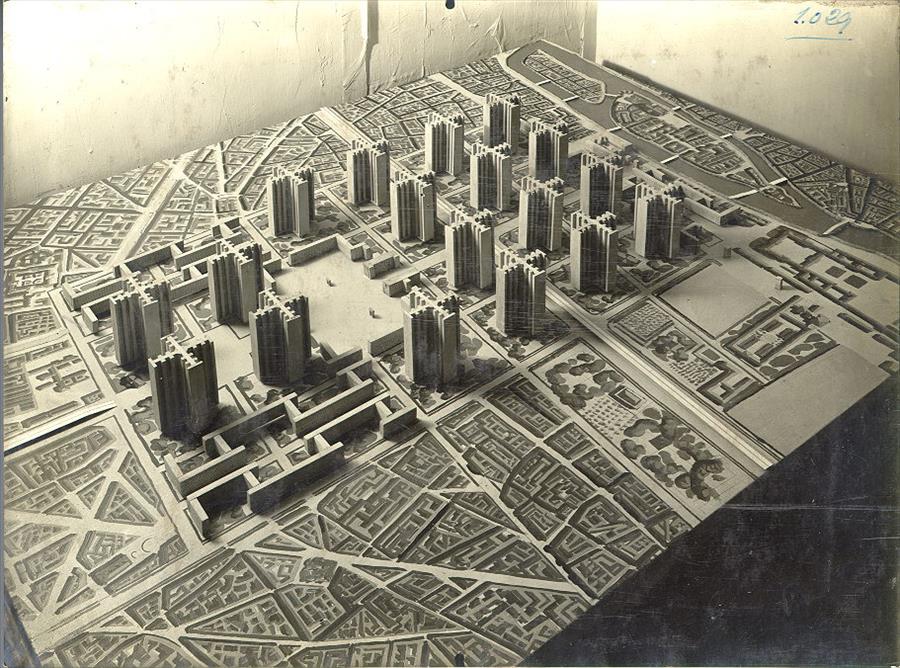

According to Corbusier, both the house and the city should operate as a machine. In case of the house, this is achieved through mass production, using new materials like reinforced concrete and steel. The idea was to make home ownership more prevalent, so that houses will be no longer an “archaic entity”[3] but rather “a tool as the motor-car is becoming a tool.”[4] Corbusier’s visionary thinking also extended to city planning, where he imagined the urban fabric to function like a machine, with dense high rises designed in a Cartesian grid, with a layout that is symmetrical and full of uniform repetitions. These ideas were formalized in his unbuilt yet influential masterplan for Ville Radieuse, also known at The Radiant City.

Corbusier’s urban vision, although unrealized, ended up influencing many major developments in modern urban planning. Some attempts were made to implement concepts from The Radiant City, in Brasilia by Oscar Niemeyer and Lúcio Costa, and in Chandigarh by Corbusier himself.[5] In the United States, Corbusier’s vision was applied in urban renewal schemes and housing projects. However, with its almost authoritarian and rigid design proposal, his visions for the modern city failed in the long run, as it ignored occupants’ needs and lifestyles.[6] One such example is the Pruitt-Igoe apartments in St. Louis, Missouri, designed by Minoru Yamasaki in the 1950s. The complex began deteriorating in the 1960s due to poor maintenance and ventilation, and ultimately became a site for crimes and vandalism. And thus, it was demolished two decades later, an event which was described by architectural historian Charles Jencks as the day “modern architecture died.”[7]

Kevin Lynch’s The Image of the City, published in 1960, seemed to be written to counteract the urban vision imagined by Corbusier. While Corbusier focused on standardization and rigidity in planning, Lynch prioritized imageability, legibility, and the presence of the city’s inhabitants. Thus, his theories were more of a response to urban renewal schemes in the United States which led to the displacement of occupants in order to impose an industrialized aesthetic. According to Lynch, there is a public image of any given city that is composed by overlapping many individual images, where each individual image is unique. And hence, he classified the contents of the city images into five types of elements: paths, edges, districts, nodes, and landmarks.[8] In Lynch’s theory, landmarks are a key element in establishing imageability of a city, but, for a city dweller, there should also be an awareness of how landmarks can serve as a means to reinforce political ideologies or power structures. In the United States, the recent discourse around confederate monuments is an example of how important landmarks, power, and politics can overlap. Those who support removal of such monuments argue, that these landmarks have no real position in present political discourse as they represent white supremacy. However, some also argue that removal of such monuments will lead citizens to collectively forget the country’s racist past, which can result in a distortion in comprehending political history, and not acquiring lessons from past mistakes.[9] This brings into question, how can these five elements of city imageability be utilized in a way that ensures a more inclusive and equitable urban landscape, both for the present and for the future?

[1] Corbusier, Le. Towards a New Architecture, trans. Frederick Etchells. (New York: Dover Publications, 1986) pg. 143

[2] Corbusier, p. 3

[3] Corbusier, p. 263.

[4] Corbusier, p. 237.

[5] Merin, Gili. AD Classics: Ville Radieuse / Le Corbusier. (ArchDaily, 2013).

[6] Unknown author, Remember: The Failure of The Radiant City. (Harlem+Bespoke, 2010).

[7] Marshall, Colin. Pruitt-Igoe: The troubled high-rise that came to define urban America – a history of cities in 50 buildings, day 21. (The Guardian, 2015)

[8] Lynch, Kevin, The Image of the City, (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1960), p. 46.

[9] Forest, B., & Johnson, J. Confederate monuments and the problem of forgetting. (Cultural Geographies, 2019). pp. 127-131.